A hanged man was never more popular. One hundred years ago, the British government executed Roger Casement for his participation in a rebellion in Ireland, the Easter Rising of 1916. This year, schoolchildren and tourists by the thousands have visited Casement’s gravesite in Dublin. It is part of a centennial pilgrimage in honour of the Rising, the pivotal event in modern Irish history, marked by headstones, prisons, and rebel redoubts now hard to imagine in jostling traffic. As the First World War raged across Europe, Irish men and women joined the Rising in an attempt to break from a United Kingdom that had bound Ireland for 115 years. In fighting to establish an Irish republic, they battled not just the British government; they also faced the prospect of a civil war against Irish Protestant unionists in the northern province of Ulster who had already spent three years arming themselves against the prospect of political domination by Ireland’s Catholic majority. In the aftermath of the Rising, the British government executed 16 rebel leaders, including Casement. He was hanged and buried on August 3 in the yard of Pentonville Prison in London, England, a land and sea away from his current resting place.

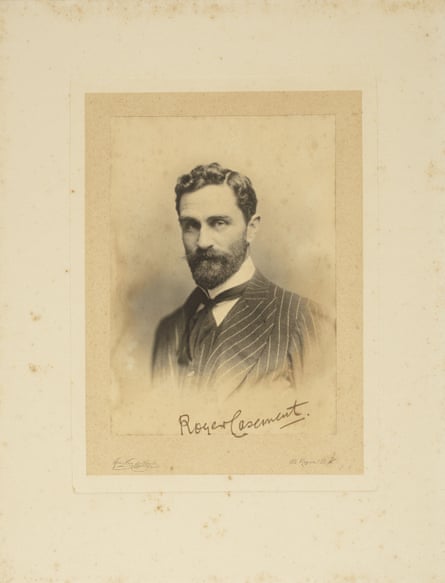

Casement, the last man to be executed, was the first among traitors in the eyes of British officials. Many knew of Casement, an Irish Protestant born outside of Dublin, for his years of work as a Foreign Office official in Africa and South America. This was the Casement who had held a memorial service in a mission church in the Congo Free State in 1901 to commemorate the passing of Queen Victoria; the Casement who was knighted by Victoria’s grandson King George V in 1911 for his humanitarian campaigns on behalf of indigenous peoples on two continents; the Casement who retired from the Foreign Office in 1913 on a comfortable pension that financed his turn to rebellion.

Just over half a century ago, in 1965, Casement’s remains were reinterred, following a state funeral, in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. This traitor to the British crown and martyr for the Republic of Ireland remains a memory in motion, stirred by an unforeseen combination of circumstances. The achievement of legal equality for gays in Ireland in 2015, together with the United Kingdom’s recent Brexit vote to leave the European Union, may occasion a new life after death for Casement — as the symbol of a united Ireland. It is the role he had hoped to play even as the trapdoor opened beneath his feet.

Since his adolescence, Casement had been an Irish nationalist of the poetic variety. But his politics hardened after his experiences in the Congo Free State persuaded him that the Congolese and Irish peoples had suffered similar injustices, both having lost their lands to imperial conquest. Like many Irish nationalists, Casement turned to militancy in the years before the First World War, angered both by unionists arming themselves and London’s failure to act upon parliamentary legislation for “home rule,” which would have granted the Irish a measure of sovereign autonomy. In 1914, Casement crossed enemy lines into Germany. There, he attempted to recruit Irish prisoners of war to fight against their former British commanders and sought to secure arms from the Kaiser for a revolution in Ireland itself. Two years later — less than a week before the Rising began — Casement was arrested after coming ashore on the southwest coast of Ireland from a submarine bearing German weapons and ammunition. He was sent to London to be interrogated and tried for treason.

These days, Casement is chiefly known as the alleged author of the so-called Black Diaries, which are at the center of a long-standing controversy over his sexuality. As Casement awaited execution in London, supporters in the United Kingdom and the United States lobbied the British government to commute his sentence. In response, British officials began to circulate pages from diaries, purportedly written by Casement in 1903, 1910 and 1911, which chronicled in explicit terms his sexual relations with men. Among mundane daily entries are breathless, raunchy notes on Casement’s trysts and, often, the dimensions of his sexual partners. An excerpt from February 28, 1910, Brazil: “Deep screw to hilt … Rua do Hospicio, 3$ only fine room. Shut window. Lovely, young — 18 & glorious. Biggest since Lisbon July 1904 … Perfectly huge.” UK law forbade any sexual relations between men, so, the government reasoned, how could any right-thinking person defend a sodomist? The diaries served to weaken support for clemency for Casement. In the aftermath of his execution a decades-long debate over the authenticity of the diaries ensued.

The leading participants in the debate are two biographers: Jeffrey Dudgeon, who believes that the diaries are genuine and that Casement was a homosexual, and Angus Mitchell, who thinks that the diaries were forged and that Casement’s sexual orientation remains an open question. The stakes of this debate were once greater than they are today. As the debate over the Black Diaries gathered momentum in the 1950s and reached a crisis point in the run-up to the repatriation of Casement’s remains to Ireland in the 1960s, Ireland was both more Catholic in its culture and less assured of its sovereign authority than it is today. The southern 26 counties of Ireland declared themselves the Republic of Ireland in 1949, but the British government continued to treat the Republic as a subordinate member of the Commonwealth, rather than a full-fledged European state, until 1968. In that year, responsibility for British relations with the Republic was assigned to the Western European Department of the newly amalgamated Foreign and Commonwealth Relations Office. Six of the counties of the province of Ulster have remained in the United Kingdom as Northern Ireland, riven by sectarian tension that the Republic and Britain have only ever brought to a stalemate. It is telling that the Irish government has been content to leave the diaries in the British National Archives rather than demand ownership and become accountable for their authenticity.

Casement’s path to political redemption was laid by the Gay Liberation movement. Dudgeon is not just a biographer but a protagonist in one of the movement’s crucial battles. In 1981, he challenged Northern Ireland’s criminalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adult men in a case against the United Kingdom brought before the European Court of Human Rights. The court ruled that the law at issue violated the European Convention of Human Rights, and this decision prompted the British government in 1982 to issue an Order in Council that decriminalised homosexual acts between adult men in Northern Ireland; England, Wales, and Scotland had already passed similar laws. In 1993 the Irish parliament to the south also decriminalised male homosexuality in order to bring the Republic’s law into compliance with the European Convention of Human Rights. And in 2015, the Republic became the first country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage by popular vote. The broader campaign for LGBT rights in Ireland has kept Casement much in the news and proudly represented him as a national son and father.

In their biographies, Dudgeon and Mitchell present two Casements, each with strengths and weaknesses. Dudgeon offers meticulous, well-documented detail, but his book, Roger Casement: The Black Diaries, is for insiders, reading at many points like the notes for a doctoral dissertation, without consistent chronological structure or contextual explanation for those unfamiliar with Irish history in general and Casement in particular. Mitchell likewise offers meticulous documentary evidence in Roger Casement, but within a comparatively fluid and clear narrative history that depends problematically upon his assertion that the British government, from the Cabinet to the National Archive, has pursued an insidious, sweeping policy of individual defamation over the past century.

Were the Black Diaries forged? And if so, was it the work of the British government, seeking to destroy Casement for his betrayal and to deny Ireland a heroic martyr? It must be said that Dudgeon and Mitchell both magnify Casement out of proportion to his significance as a threat to the United Kingdom, a state that was attempting to survive a war on multiple fronts, with flagging morale at home, in 1916. The government had larger fish to fry than this man who never founded or led a political party, never engaged in assassination or led men into combat, and never wrote a popular manifesto or treatise. Moreover, as Dudgeon argues, it would have been a monumental, virtually impossible task in 1916 for officials and civil servants to forge diaries so comprehensive in their account of long-past events — when Casement was not under suspicion — that they could convince even Casement’s associates, who found themselves and their own interactions with Casement mentioned in the text. In a fascinating turn, Dudgeon offers the most successful refutation of forgery to date by systematically verifying the diaries’ contents, relentlessly revealing and cross-referencing new sources to pull together loose ends and flesh out identities from cryptic references and last names, such as that of Casement’s alleged boyfriend: “Millar.” Against the historical backdrop of a government marshalling limited resources in wartime, Dudgeon effectively charges that a forgery so verifiably true to life could not have been a forgery. He is probably correct.

Yet to travel further down this historical rabbit hole risks missing what is most significant about Casement at present: his potential reinvention as a symbol of Irish unity in the future. Casement has been resuscitated by an extraordinary combination of developments in the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom, not just the relative toleration of homosexuality, but the lurch toward Brexit in a popular referendum that found 52% of UK voters in favour and 48% opposed. The decisive support for Brexit was located in England and Wales, while both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to remain in the EU, the latter by 55.8% to 44.2%. The Republic of Ireland and the UK have long agreed that the political division of Ireland will continue until the majority of Northern Ireland’s citizens vote to sanction secession. Even as Northern Ireland has moved steadily toward a Catholic majority (most of whom support secession), there is still a sizeable minority of Catholics who prefer continued union with Britain in the name of economic and political stability. After the Brexit vote, the disparate communities of Northern Ireland — Protestants and Catholics of all political stripes — may find new common ground in, of all places, Europe. Northern Ireland, like the Republic, benefits substantially from its relationship with the EU, and nationalists and unionists alike are worried about the loss of EU subsidies and markets.

In the days preceding his execution, Casement asked his family to bury his body near the home of relatives in County Antrim, in what is now Northern Ireland. This was the family that had taken young Roger in after an itinerant childhood and the deaths of his parents. “Take my body back with you and let it lie in the old churchyard in Murlough Bay,” he reportedly stated. Casement’s reinternment at Glasnevin Cemetery was, in fact, a compromise. In 1965 neither the Irish nor the UK governments wished to antagonise Ulster unionists with the burial of a republican martyr in their midst. Among the many tributes laid at Casement’s grave following his burial in Glasnevin was a sod of turf from the high headland over Murlough Bay.

The transfer of Casement’s remains from Pentonville to Glasnevin was conceived by the Irish and UK governments as a symbolic gesture of goodwill that would set the political stage for the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement of 1965. The governments turned to each other for economic support because France had frustrated their attempts to gain entrance into the European Economic Community (EEC), the predecessor organisation of the EU. When both countries joined the EEC in 1973, this trade agreement lapsed. Once more, then, with Brexit, Casement’s bones have been stirred by Anglo-Irish relations with Europe. In Ireland, the effects are likely to be much different this time around. In representing Casement as a man of contradictions, biographers have assessed him in the terms of conflicts in Irish society that persisted long after his death: the sectarian divide between Protestants and Catholics, the troubles between Ireland and Britain, and the discrimination against male homosexuals enforced by religion and law. As these conflicts dissipate, Casement will be recast in a new light. The portrait of a man of contradictions will give way to a composite picture in which the majority of the people of Ireland may see themselves. Should Ireland reunite, whether in the aftermath of Brexit or in a more distant time, the moment of reconciliation, of acceptance and forgiveness, may well occur over a grave at Murlough Bay.

*****

Kevin Grant is a professor of history at Hamilton College and is currently completing a book on hunger strikes in the British Empire. He is the author of A Civilised Savagery: Britain and the New Slaveries in Africa, 1884–1926 (2005) and other works on empire and humanitarian politics.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion